I was called ignorant for the first time in my life this past Sunday. I was at a family and friends gathering when someone said they are not a negro. Someone else said they were a Moor, and another said they were African. That’s when I said, “I am Black, but not African.” What followed was an emotional conversation about whether or not we, Black people, are African. No one in the room agreed with my point of view, and so followed the labels of ignorant and divisive. This was hurtful coming from a room full of people I love, respect, and in some cases admire. I woke up the next day thinking about our conversation, and again the next day, which is what led me to this blog post. I had to get my thoughts out. First, I want to explain who I am for context.

Where Are You From?

As an adult, it’s been difficult for me to answer the question, “Where are you from?” I was born in Evanston, Illinois, a suburb just north of Chicago, to a Jamaican mother and Dominican (Dominica, not the Dominican Republic) father who somehow ended up in Jamaica in his teen years. My parents’ relationship didn’t last long. They broke up soon after I was born and my mother met another man, also Jamaican, whom she eventually married and moved to South Florida with. They were together for the first twenty years of my life. With my biological father mostly out of the picture, my stepfather raised me. I lived the first four to five years of my life in Chicago before moving to Miramar, Florida.

If you asked me where I was from as a child, without hesitation, I would say Jamaica. My parents spoke patois, cooked only Jamaican food, and listened only to Jamaican radio. The only friends we had were other Jamaicans. That’s the culture I identified with most. Most of my mother’s family had left Jamaica and had been split between London and Chicago by that time. My stepfather’s entire family still lived in Jamaica, St. Elizabeth to be exact. I spent every summer of my childhood in Jamaica, London, or split between both places.

I am now in my 40s and don’t spend summers away from the United States. Looking back at my childhood, I think all of these places shaped the person I am. All of these places are where I am from. Africa is not one of them. I am not Ethiopian, Moroccan, Kenyan…I know that we, Black people, descended from Africa, but I never thought of myself as African, those are two different things. In fact, I didn’t think about the differences between Black people in the Western world and those in Africa until I moved to London for a year in 2013 to complete a master’s program at Middlesex University.

London at 30

I moved to London at the beginning of 2013, when I was 30 years old to complete a Master of Arts in Marketing Management at Middlesex University. My family in London lives in Brixton, South London. This is where I always stayed when in London. 1990s and early 2000s Brixton was gritty but charming, mostly Caribbean, and had the best parties – I loved it. I lived in Colindale when I moved to London in 2013, a neighborhood on the city’s northwest side that borders Hendon, where Middlesex is. I wasn’t familiar with the area and it wasn’t like Brixton. Colindale has larger homes, is quieter, and has a more diverse population than Brixton.

Middlesex’s population was like its surrounding area. It seemed that every nation on Earth was represented there. Naturally, I looked for other Black people. Almost every Black person on campus was African, mostly Nigerian. Two of my flatmates, whose names I can’t remember, were also Nigerian. There was one other Black girl in my cohort, Emily. Emily is one of my best friends now. My flatmates and I had conversations in our shared kitchen about life in our home countries. I hung out with other Nigerians and Ghanaians that I met at school too. We ate lunch at the restaurants in the area and studied together. This was my crew, the people I spent time with every day. They asked me about strip clubs, the ease or difficulty of buying sneakers, and high school in the United States.

Our interactions taught me about West African culture. They spoke in different languages, ones I wasn’t familiar with. Listening to them describe someone, they always mentioned the tribe the person belonged to – Igbo, Hausa, Fulani…I didn’t realize that Nigeria had such a large Muslim population until then. My friends from the southern part of Nigeria complained about greed in the northern part of the country. They explained to me the role of the emirs and spoke of Fela Kuti as if he was the coolest man that ever lived. They joked about which jollof rice was better, Nigerian or Ghanaian. This was new to me. I don’t have a tribe. My home country doesn’t have emirs or anything close to them. I had never had jollof rice or even heard of Fela Kuti before then. I was different, we were different.

Tension

My Nigerian and Ghanaian friends were warm and welcoming toward me, but I sensed that Black-British people didn’t get along as well with them. For example, with a look of disdain, one of my cousins asked me why I had made so many African friends. Also, a friend of a friend commented that she thought the town of Stevenage, 20 minutes north of London, was nice except for the fact that there were a lot of Africans living there. I’ve always been interested in the human experience, societies, and cultures. I wanted to better understand what was behind this so I asked Emily. She told me that some Black-British people think Africans look down on them. She recalled being called “BBC” which stood for Black British and Confused, by African immigrants and first-generation Afro-British students in school.

After speaking to Emily, I asked my Nigerian friends if this was true. Did they look down on Black-British people? One friend told me that a lot of Africans think British people, including Black-British people, look down on them. She said they may say things like “BBC” as a defense, like, “How can you look down on me when you don’t even know who you are?” Another friend said that Africans look at us, Black-American and Black-British, as weak. He said we descend from the weak and that’s how our ancestors were sold into slavery. This is the opinion of a few people and doesn’t represent all of West Africa or the diaspora, but I was shocked to hear these opinions at all!

Fast Forward

Fast forward to June 2022. I visited Accra and Cape Coast, Ghana. I was shocked that Ghana reminded me of Jamaica. The countries have similar topography and climate, but it was more than that. I’d never seen so many ackee trees outside of Jamaica before. Women selling breadfruit on the side of the road, hard dough bread at breakfast and sorrel to drink. Men called out “Empress,” as I walked past. Cape Coast in particular felt like Jamaica. I was moved to tears a few times on that trip because I had found my roots. After my experience there, there’s no doubt in my mind that Ghana is where Jamaicans came from. Still, I wouldn’t say I am Ghanaian. My children and the generations after them won’t have the same connection to Jamaica as me because they won’t experience Jamaica the way I did. I now have more family living outside Jamaica than living inside. America is my family’s home now and the longer you stay in a place, the further you get from where you came.

The experiences I recounted here are why I say I am Black, not African. The language you speak, the foods you eat, and your traditions and values are what make you who you are. I don’t have these things in common with Africans on the continent now. We are similar, but not the same. What I got from Africa are my biological characteristics – my skin, nose, my DNA. These are the things that all Black people have in common. I’m not trying to distance myself from Africa and Africans. I just think that Black people in America and other parts of the diaspora are more distant from Africa than we think we are.

*A note about conversations mentioned in the article. I can’t remember the exact words that were said in some cases, but I remember the context of the conversation and wrote about it to the best of my recollection.

“Our schools are not an equalizing force, because White parents take them over and hoard resources,” this quote from the introduction of episode four sums up Nice White Parents, a podcast from Serial Productions, a New York Times company. The quote is about Horace Mann’s idea that public school would be the great equalizer of American society.

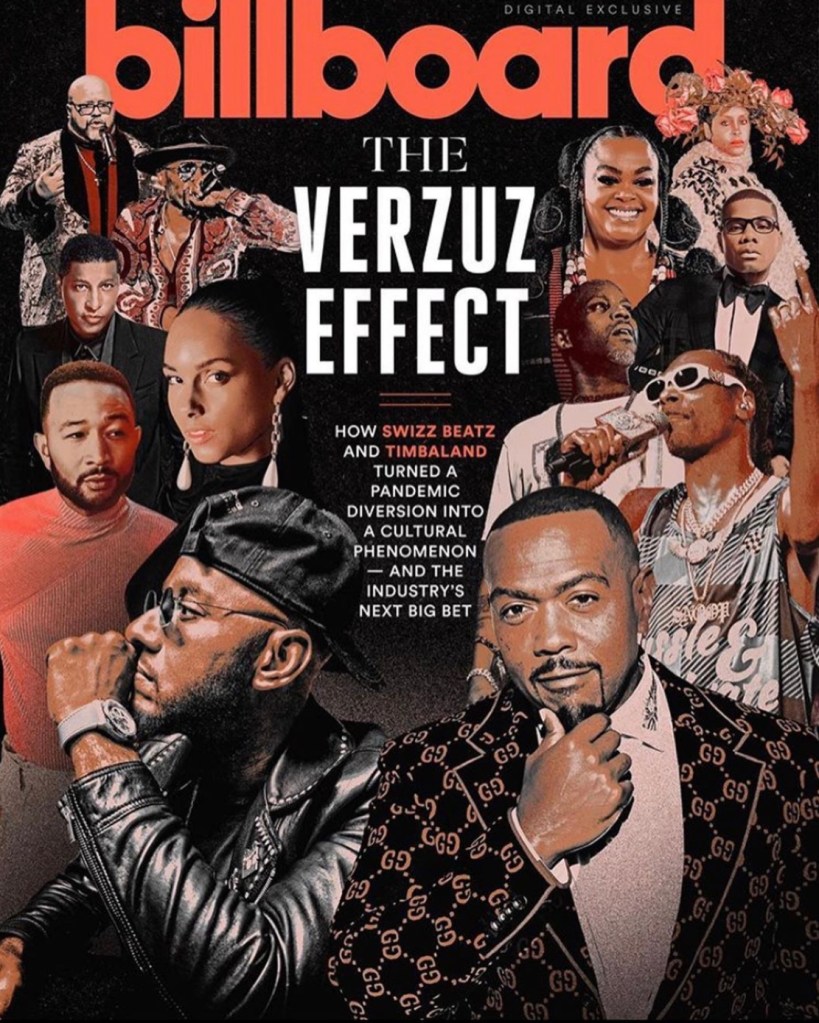

“Our schools are not an equalizing force, because White parents take them over and hoard resources,” this quote from the introduction of episode four sums up Nice White Parents, a podcast from Serial Productions, a New York Times company. The quote is about Horace Mann’s idea that public school would be the great equalizer of American society. As the pandemic drags on keeping concert venues and other entertainment shut down, thousands of people log in to watch artists “battle” each other week after week on Verzuz. On Tuesday, August 11th I was doing my morning check of social media handles when I came across a post from Sharon Burke, President of Solid Agency, a management and booking agency in Kingston, Jamaica. Ms. Burke is a giant in the dancehall music industry (She’s also my cousin). Her clientele includes Bounty Killer, Sean Paul, and Shaggy among others.

As the pandemic drags on keeping concert venues and other entertainment shut down, thousands of people log in to watch artists “battle” each other week after week on Verzuz. On Tuesday, August 11th I was doing my morning check of social media handles when I came across a post from Sharon Burke, President of Solid Agency, a management and booking agency in Kingston, Jamaica. Ms. Burke is a giant in the dancehall music industry (She’s also my cousin). Her clientele includes Bounty Killer, Sean Paul, and Shaggy among others.

![johncoulter_perfect_chemistry_lcs[1]](https://kamariaskiss.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/johncoulter_perfect_chemistry_lcs1.jpg?w=228)

![no_social_media[1]](https://kamariaskiss.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/no_social_media1.jpg?w=300)